Glace Plombières – A French classic

Few ice creams have made it into the world literature. And fewer still can trace their origins back to a dinner with Emperor Napoleon. Say ‘hello’ to a true French ice cream classic: Glace Plombières.

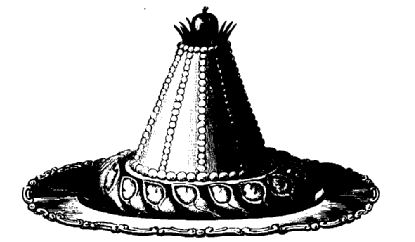

“Plombière” might sound like a fancy French word, but is actually what you would call a female plumber (in French). But there are other meanings too, and the ice cream flavour-one is likely derived from the word for the metal lead (“plomb“). Luckily, the lead in question has nothing to do with the ingredients as such – instead, it refers to the leaden ice cream moulds that were used in the old days.

But important for the story, there is also a French municipality that uses the word in its name – Plombières-les-Bains, known for its thermal baths … and a secret, diplomatic pact! But more of that later on.

A famous Italian confectioner, Tortoni, offered “plombière” desserts in Paris already in 1798. Whether the name of the dessert mainly referred to the moulds, or rather tried to capitalise on the fame of the then fashionable thermal baths of Plombières-les-Bains, is difficult to ascertain. At the time, the recipes were apparently made up of almond milk, eggs and fruit, and with a consistency closer to icy granitas than to typical ice cream.

In its heydays, Café Tortoni was the best place for frozen desserts in Paris. Actually, it was a vastly popular place even for those who did not particularly care about ice cream – artists, painters, politicians, the wealthy … practically everyone flocked there. And towards the mid-1800’s, the ice cream plombières (or, as we shall see, at least a precursor) even made it into the world literature:

“At the end of the meal ices were served, of the kind called plombieres. As everybody knows, this kind of dessert has delicate preserved fruits laid on the top of the ice, which is served in a little glass, not heaped above the rim. These ices had been ordered by Madame du Val-Noble of Tortoni, whose shop is at the corner of the Rue Taitbout and the Boulevard.”

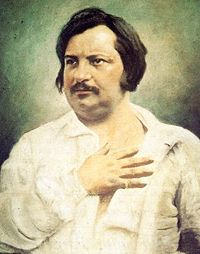

If you know your French literature, perhaps you recognise the book? (The portrait of the author and Manet’s painting below might give you a hint about the title …)

Yes, it is from “The Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans“ (also known as “A Harlot High and Low”) by Honoré de Balzac, one of the real giants of French literature. The book came out in parts during the years 1838-1847. And while Tortoni probably not was the only one experimenting with “plombière”-desserts in Paris at this time, it is his creation that has gone down in literary history.

One ice cream, two spellings … or ?

But what about the spelling? Balzac wrote about “plombiere” (at least in one place in the French original) but the ice cream still found today is called “plombières“.

While the first spelling probably referred to the ice cream mould, the second one is more likely to refer to the French municipality of Plombières-les-Bains, famous for its thermal baths. And some would say that what happened there an evening in July 1858 indeed was the ‘crowning event’ of a culinary ice cream development that had started in Paris by Tortoni and others.

Secret treaties and ice cream fit for an Emperor?

According to ice cream lore, the ice cream found its defining form at an illustrious dinner on 20 July 1858. However, as with a lot of ice cream lore, be warned that this very popular story actually may be totally wrong! As it is a good one, and quite widespread, I will tell it anyway – if nothing else, you can always express your sound skepticism whenever you come across the tale in the future.

That there was a dinner that evening in July 1858, and that a secret treaty was discussed there is certain. Present were French Emperor Napoleon III and Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour and a leading man in the struggle for Italian unification. The two had come together in the French commune of Plombières-les-Bains to negotiate a secret treaty: In return for its help towards a unified Italy and against Austria, France would receive Nice and Savoy. The rest of the story, however, dealing with the birth of the ice cream that very day, is harder to verify.

According to the story, the chef responsible for the dessert that evening had a bad day. He had apparently planned to serve a new custard-type dessert – but the custard sauce collapsed! The failed consistency was no longer fit for presentation, and the chef had to improvise in order to save the situation. This he did by frantically whisking the custard sauce together with some added kirsch. When the consistency seemed acceptable, he added some candied fruit and froze it all – Glace Plombières in its classic form was born!

The rest was, as they say, history. But even if the imperial dinner-story might just be a good story, the special tradition alive to this very day in France can at least be traced back to 1882. That year, a local confectioner, monsieur Philippe, was credited with the innovation of macerating the candied fruit in kirsch (another regional specialty, by the way!) before adding them to the ice cream – a measure that since then became the new standard.

Generations of local chefs in Plombières-les-Bains have perpetuated the production by following the original recipe. Luckily for us, however, this recipe is not a well-kept secret. The guardian of the tradition at the time when this post first was written, monsieur Michel Bilger, owner of the since-then closed hotel-restaurant La Fontaine Stanislas in Plombières-les-Bains, had kindly shared the classic recipe at occasions.

The classic recipe – after Michel Bilger

To my surprise, the ‘canonical’ recipe is based solely on three structural base ingredients: milk, sugar and egg yolks. And let me tell you that this cream-less ice cream base manages to combine a really nice texture and consistency with a delicious taste.

If you ever would like to try how good milk-flavoured ice cream can be, this should be your preferred recipe!

Towards the end of the churning add candied fruits, macerated in high-quality kirsch for at least half an hour, to the ice cream base. Ideally, the candied fruits should be cut in small cubes and come in at least three different colours (Bilger suggests cherries for red, pineapple for orange, and lemon or angelica for green).

Candied fruit … they should spend some time soaking up high-quality kirsch before being added to the ice cream base towards the end of the churning

Raw milk or pasteurised?

I have read two different accounts of Michel Bilger’s recipe, and one of them makes clear that the milk to be used should be raw (the other version remains somewhat ambiguous on this point). After all, this is perhaps not too surprising. Firstly, because the recipe is old, and secondly because I have heard that some French connoisseurs consider the use of raw milk to be one of the key secrets behind really great ice cream. It would also explain why the first step in the recipe is to ensure that the milk has been boiled – In my view, this step seems quite unnecessary, provided that you use pasteurised milk.

Still, since there are several (at least potential) health hazards connected with using raw milk, I would advise you to stick to pasteurised milk (or perhaps try to find some low-pasteurised milk, which I have seen on sale in some places). Mind you – in many places you would probably even have a hard time finding any raw milk for sale. If you remain keen on using raw milk, do heed the first instruction and make sure to boil it before using it!

The final result

It is easy to understand that this flavour has managed to stay popular for over 150 years. The all-milky ice cream base is delicious already on its own. The addition of the colourful candied fruits – their flavours enhanced and made more complex by maceration in kirsch – finally define the delicious overall taste of the ice cream.

Similar ice cream flavours exist outside of France. There, “Tutti frutti” remains a popular overall label for ice creams mainly flavoured by candied fruits. It seems quite clear, however, that the French original recipe for glace plombières does set it apart from many ‘simpler’ versions. And in case you fear that the ice cream would be too sweet for your refined taste, why not try adding a teaspoon or two of finely grated ginger (or a tablespoon of candied ginger) to the mixture? While not really canonical, it would certainly put a little extra spicy spin to the traditional recipe.

Still quite soft straight after the churning – if you prefer more solidity, let the ice cream spend some time in the freezer.

- 1000 ml (4 cups) whole milk

- 300 grams (about 1½ cups) powdered/confectioner's sugar

- 6 egg yolks

- 200-250 grams candied fruits (preferably of at least three colours)

- 100 ml (about 0.4 cup) Kirsch of high quality (for macerating the candied fruits)

- Boil the milk [Note: likely unnecessary, if you use pasteurised milk!]

- Put the milk, the sugar and the egg yolks in a saucepan. Bring the mixture to a temperature of either 70°C (158°C F), or to a maximum of 85 °C (185° F) [to avoid health hazards, keeping to the higher end of the spectrum seems the safest option]. While cooking the base, keep whisking it with a spatula - Bilger suggests moving it around in the pattern of "eights", which seems sensible.

- When ready, chill the base as quickly as possible [Bilger's original recipe calls for a rapid chilling to -20 °C (-4°F), accomplished by pouring the hot base straight into an ice cold ice cream maker to chill. This last part is probably not to be recommended for home ice cream makers].

- Churn the ice cream base. When almost done, add the candied, macerated fruits. Finish the churning.

- Store the finished result in the freezer.

As we are on vacation in France we are close to “Plombières” Passing this place a few times this week, I came to say to my wife in my opinion Plombières is also an icecream

(I think I read it a long time ago in a book may be G de Maupassant :-)) . Looked at the internet found your site where you informed us with lots of well-thought information about Plombières.

However as a nozy Dutchman and certainly not that well informed as you are, I have additional information!

As the recepy contains KIRSCH, please note, Plombières is in the centre of the region famous for KIRSCH so I think it is named to the city as you also sidely mention. Kind regards Henk van der Have from the Netherlands

Dear Henk,

That’s correct – The region is famous for its Kirsch (with the commune Fougerolles considered to be the French ‘Capital of Kirsch’), so it was probably no mere coincidence that this particular liquor came to be part of the recipe. Thanks for posting and hope you’re enjoying the region (and possibly even the ice cream 😉 ).

Boiling milk alters the protein structure, allowing it to hold on to water better, which leaves less water available to form ice crystals.

Interesting! I have also read somewhere that boiling milk makes it easier for humans to digest (by breaking down the proteins into easier-to-digest amino acids).

Hi there! We feature this lovely recipe on our Instagram if you’d like to check it out: https://www.instagram.com/p/CQbattKL_FA/

We gave it a try and thought it turned out great! Perfect for the summer solstice.